Urchin Invasion

How sunflower sea stars could bring back life to the Oregon Coast

We traveled to the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology (OIMB), located two hours south of Eugene in Coos Bay, Oregon. This satellite campus serves as a working marine lab located on the Pacific Ocean. The surrounding area includes multiple state parks and reserves. Classes frequently take field trips to Cape Arago State Park, specifically South Cove, where this story begins.

The morning began bright and early. We hoped to catch the low tide, eager to see the varying types of marine life that call South Cove home. Departing from OIMB, we drove twenty minutes up Cape Arago Highway; looking out the windows, we saw a never-ending coastline. Once we parked the car, we started down the trail to South Cove, which had dried up. When we reached the sand, we started trekking towards the right side of the cove. The view in front of us was breathtaking; everything was untouched, waiting to be explored. With each step, the rhythmic crash of waves grew louder as we descended toward Drake’s Point, the furthest reach of the cove.

The beginning of our trek was filled with slippery seaweed covering the rock, requiring careful navigation using the three-point method—where you use three points of contact (hands and feet) to maintain balance. Around us, a vibrant array of marine life unfolded. Snails clung to the rocks, nudibranchs displayed colorful patterns, kelps swayed gently in the water, and sea stars and anemones filled the tidepools. Every new creature we found brought a new sense of awe.

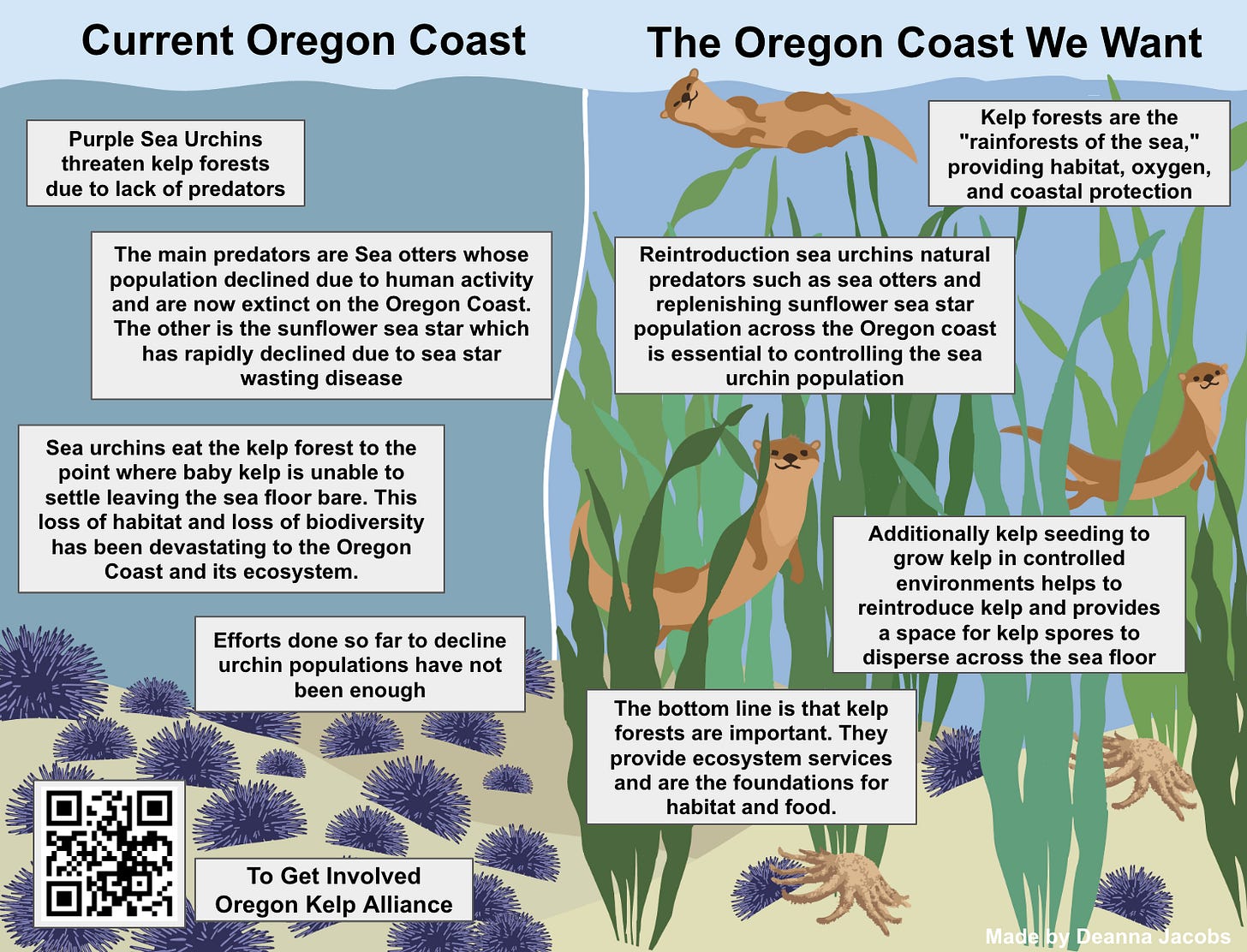

As we ventured further, purple began to dominate the scene. At first, it was subtle—a patch here, a speck there, but soon it was impossible to ignore. Purple sea urchins covered the rocks in overwhelming numbers, transforming the tidepools from a vast array of colors to a spiny purple expanse. At OIMB, we’d been taught that if you lose your balance, stepping on urchins isn’t just safe—it is also our way of helping to combat their overpopulation as these purple urchins have expanded far and wide across the Oregon Coast, devastating Oregon’s kelp forests, turning a thriving ecosystem into a barren wasteland.

Standing at the edge of South Cove, surrounded by an overwhelming amount of purple spines, I couldn’t help but think about the vital work being done just a few miles down the road at OIMB by Dr. Aaron Galloway, a marine ecologist who focuses on kelp forest ecology and sunflower sea star recovery. Galloway’s work explores the intricate relationships within kelp forest ecosystems, focusing on potential solutions to counter the devastation caused by the overpopulation of purple sea urchins. One of his most promising areas of study involves the sunflower sea star, a predator whose recovery could hold the key to restoring balance to the kelp forests.

Unlike sea otters, another keystone predator, sunflower sea stars have a unique advantage: their capacity for rapid exponential growth. “Unlike sea otters, sunflower sea stars have the potential for rapid exponential growth, with each adult producing millions of eggs under the right conditions,” Galloway explains. By investing in the recovery of these sea stars, we can harness their natural ability to control the urchin populations that threaten to turn the vibrant underwater forests into barren wastelands.

But the path to recovery is steep. Between 2013 and 2015, sunflower sea stars were nearly wiped out by sea star wasting disease, with a staggering 99% loss along the Oregon Coast. Galloway and many scientists are still unraveling the inner workings of this disease, but one thing for sure is that it was heightened by rising ocean temperatures linked to climate change. This warming perpetuates a deadly cycle: kelp decline, unchecked urchin populations, and biodiversity loss.

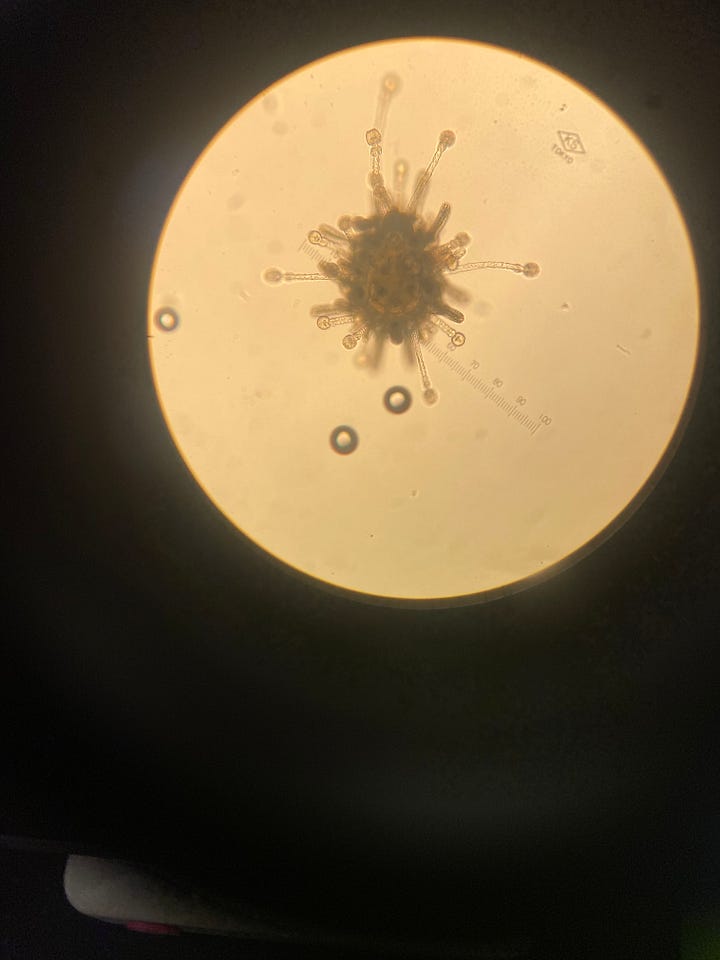

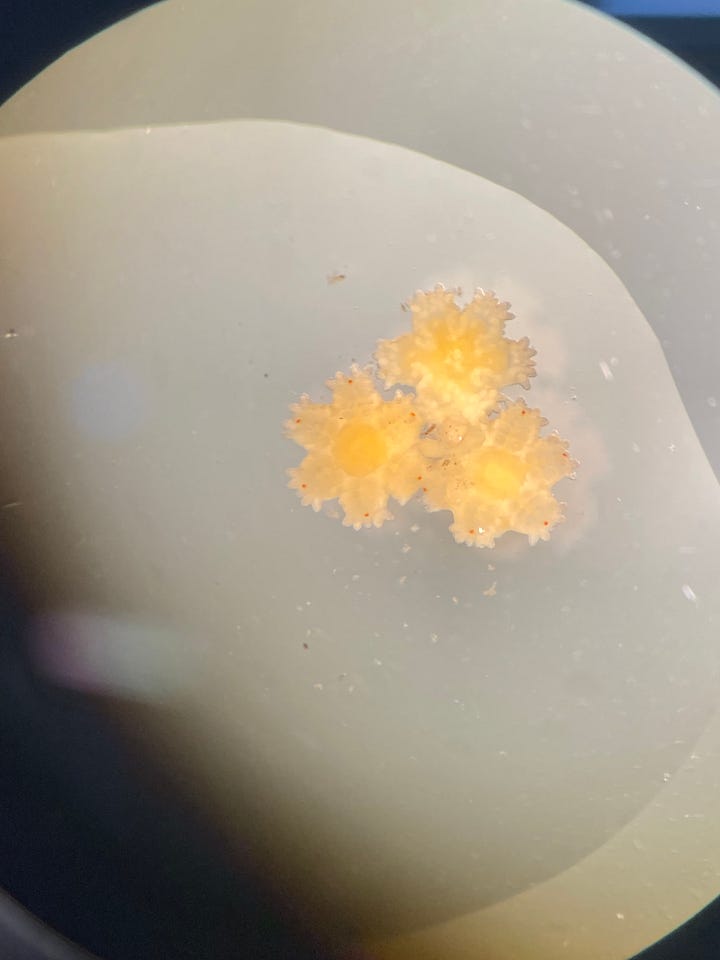

Despite these challenges, Galloway remains focused on the future. He has identified four potential levers to restore kelp forests: reducing carbon emissions, manually culling urchins, seeding kelp, and predator recovery. Of these, he explained how predator recovery offers the most promise, mainly through the reintroduction of sea stars—the primary focus of his lab. Not only are sunflower sea stars a natural predator of purple sea urchins, but they are also good at predation. In a recent study, Galloway observed that a single sunflower sea star can consume five urchins in seven days. Their reproductive capacity makes them promising; under the right conditions, sunflower sea stars can release millions of eggs into the water column, a crucial advantage in combatting the explosive reproduction of purple sea urchins, which release up to 20 million eggs annually.

Within the last month, the Oregon Kelp Alliance (ORKA) received extensive funding from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). ORKA has appointed Galloway’s lab to lead research into predator loss and reintroduction, furthering his efforts to restore balance to the ecosystem. While Galloway’s primary research is on sunflower sea stars, he is also an avid supporter of sea otter reintroduction on the Oregon Coast. He works closely with the Elakha Alliance, an Indigenous nonprofit organization dedicated to reintroducing sea otters to the Oregon Coast—an effort deeply tied to restoring kelp forests and the biodiversity they support.

ORKA and the Elahka Alliance are trying to restore these keystone predators. The Elakha Alliance refers to sea otters as “climate warriors” for their vital role in maintaining productive, biodiverse coastal ecosystems. “The whole ecosystem depends on that species being there to function properly,” says Chanel Hason, a marine biologist and sea otter recovery advocate for the Elahka Alliance. Reintroducing sea otters is a long-term solution. Populations grow slowly, and females typically have only one pup per year, so their return represents hope for Oregon’s coastline. The Elakha Alliance collaborates with state and federal agencies, including the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), to develop sustainable reintroduction plans requiring significant resources and community support.

At the same time, Galloway’s lab is leading efforts to bolster the recovery of sunflower sea stars through its partnership with ORKA. Alongside predator reintroduction, Galloway emphasizes interconnected restoration strategies, including manually culling urchins, seeding kelp, and addressing carbon emissions. These combined efforts, he notes, require collaboration among scientists, governmental agencies, and Indigenous communities to bring Oregon’s underwater forests back to life.

Standing at the edge of South Cove, looking at the overwhelming amount of purple urchins and barrens everywhere, it is impossible not to reflect on Galloway’s words, “The bottom line is that kelp forests are important. They provide ecosystem services and are the foundations for habitat and food. Management-wise, we want to make decisions that protect or establish kelp forests.” His call to action resonates: By supporting restoration efforts, raising awareness, and advocating for sustainable practices, we can help restore the kelp forests and the vibrant ecosystems they support.

Cailin and Deanna I was so so excited to read this after your presentation last week and it did NOT disappoint. Really quick, the tide pool photography is so excellent. It makes me miss the coast desperately. And the diagram at the end is wildly helpful as well, it really brings all the concepts into a clear and easy visual. Nice job. I think the written piece is well written, easy to read and understand, and still is getting the various aspects of the science across. You did amazing on all your projects, and I hope you feel so proud of this one. Thanks :)